Guest Column from UW-Madison Division of Extension

Stress can negatively affect health, sleep, relationships and communication with others. Probably the most crucial impact is the way in which chronic stress, developed through the combination of duration and intensity, impacts decision making.

Understanding stress – and finding and using the throttles that control the flow of hormones and chemicals that fuel chronic stress – is essential for our health and the well-being of our loved ones and relationships.

All people feel short-term stress when something frightening happens – a fire in a shed; or, you learn of unexpected medical news. When we encounter acute stressors like these, stress hormones cause heart rate to increase, blood pressure to rise and spleen to release more red blood cells to supply oxygen so one can act quickly.

In short-term stress situations, the response is helpful. We are prepared to fight a threat, like calling 911 and grabbing an extinguisher to fight a fire, or we can run away from the situation. Humans have developed this acute stress response over thousands of years. It helps ensure survival.

The problem is that during prolonged challenging and stressful times over months or years, this stress response repeats itself over and over causing the brain’s thermostat mechanisms that keep these chemical releases in check to become less effective. The result becomes long-term, chronic stress that often leads to numerous health problems. The constant presence of high levels of this stress ‘fuel’ (adrenaline and cortisol) also make it more difficult to make smart and focused long-term decisions.

The problem is that during prolonged challenging and stressful times over months or years, this stress response repeats itself over and over causing the brain’s thermostat mechanisms that keep these chemical releases in check to become less effective. The result becomes long-term, chronic stress that often leads to numerous health problems. The constant presence of high levels of this stress ‘fuel’ (adrenaline and cortisol) also make it more difficult to make smart and focused long-term decisions.

The UW-Madison, Division of Extension’s Responding to Stress Initiative helps farmers, families, businesses and communities remain resilient by learning how to manage stress by recognizing and working to positively address, not avoid, the causes of stress. Thinking carefully about a situation and clearly understanding it, so you can decide what to do, is a first step to addressing the stress caused by uncertainty, and it puts you on the path to take control of decisions.

Sometimes people cannot recognize signs of stress in themselves; others might sense something is wrong but may not know how to bring it up. Start the conversation by talking with family and friends about stress and the changes that might need to happen. Resilient families view crisis as a shared challenge, instead of having each person be a ‘tough, rugged individual,’ getting through hard times. They believe that by joining together with family members and others who are important to the family, they can strengthen their ability to meet challenges. It is also important that people stay connected to the resources, friends, neighbors and support systems in their community; those can include your church, schools, ag service providers and experts.

For more tips about managing stress, visit fyi.extension.wisc.edu/farmstress.

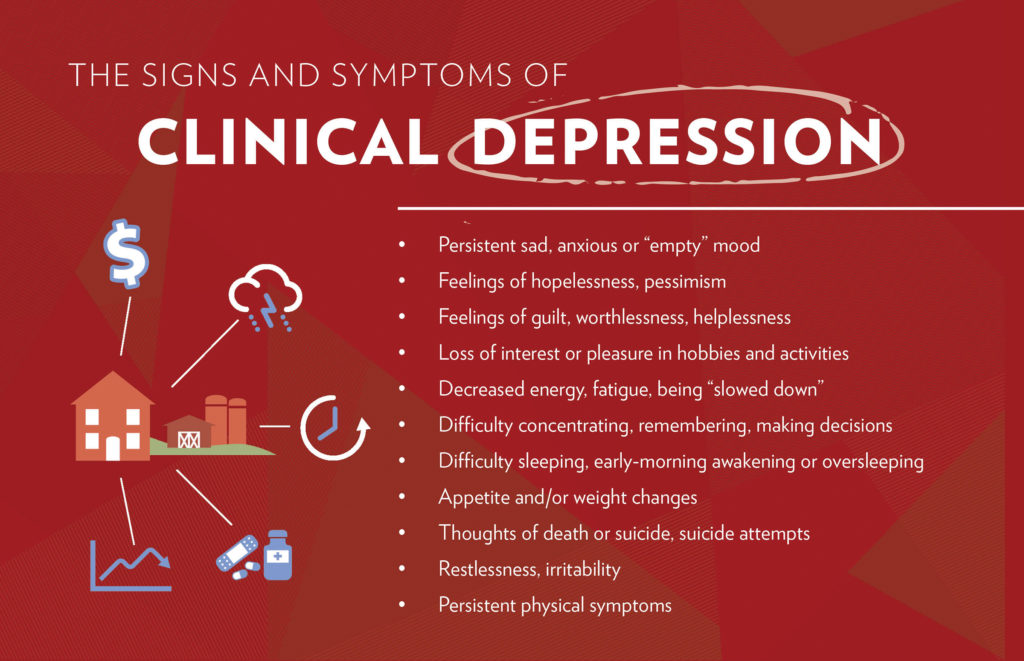

If any person expresses the signs and symptoms of extreme stress and talks about harming themselves or ending their life, it is important to provide help and support. The most important resource for support in the U.S. is the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, accessible for English-speaking people at 800.273.8255 or in Spanish at 888.628.9454. See suicidepreventionlifeline.org for more information. Those working in rural communities and providing services and support to farmers and their families should also consider completing a course in ‘Mental Health First Aid’ or ‘QPR,’ a suicide prevention program that has been shown to save lives.

This column was originally published in the 2019 June|July issue of Rural Route.

Leave a Reply